How simple early value propositions can make startup life easier.

October 7, 2025

The most cliche pitch in startup world piggybacks off of Amazon's origin story, rising to become the "everything store" of today.

"This is our books starting point..."

The pitch deck shows a massive TAM, the product roadmap sprawls across dozens of features, and the go-to-market strategy targets "all companies that need X." It's an understandable impulse, especially in a venture capital landscape where $8B+ multi-stage funds are consistently writing nine-figure checks into companies achieving $100M+ in ARR in months and ambitions of being the next “decacorn”.

The reality is more counterintuitive. Amazon demonstrated that the most successful companies rarely start by going broad. Instead, they identify a narrow market where they can become the undisputed leader, build something their initial customers genuinely love, and then systematically expand from that position of strength. This approach represents a fundamental way to build defensible, valuable businesses and yet is seemingly overlooked by many startup founders. They say "books" but they are often really non-committal on the narrow path they intend to definitively win.

The pattern is consistent across industries and decades. Start with a tightly defined segment where you can achieve market leadership. Deliver a unique solution to that specific audience. Use the resulting traction and revenue to fund expansion into adjacent markets. Repeat.

This approach works because narrow markets allow for precise targeting. When you know exactly who you're building for, you can understand their needs deeply, communicate your value clearly, and iterate quickly based on feedback. In short - you reduce your customer acquisition costs through better targeting. You're not trying to be all things to all people—you're trying to be indispensable to a specific group who understands exactly what they’re buying when they choose you.

The financial engine this creates is crucial. Early revenue from a focused market provides the resources to expand, but more importantly, it validates your ability to deliver value. You earn the right to serve broader markets by proving you can dominate narrower ones.

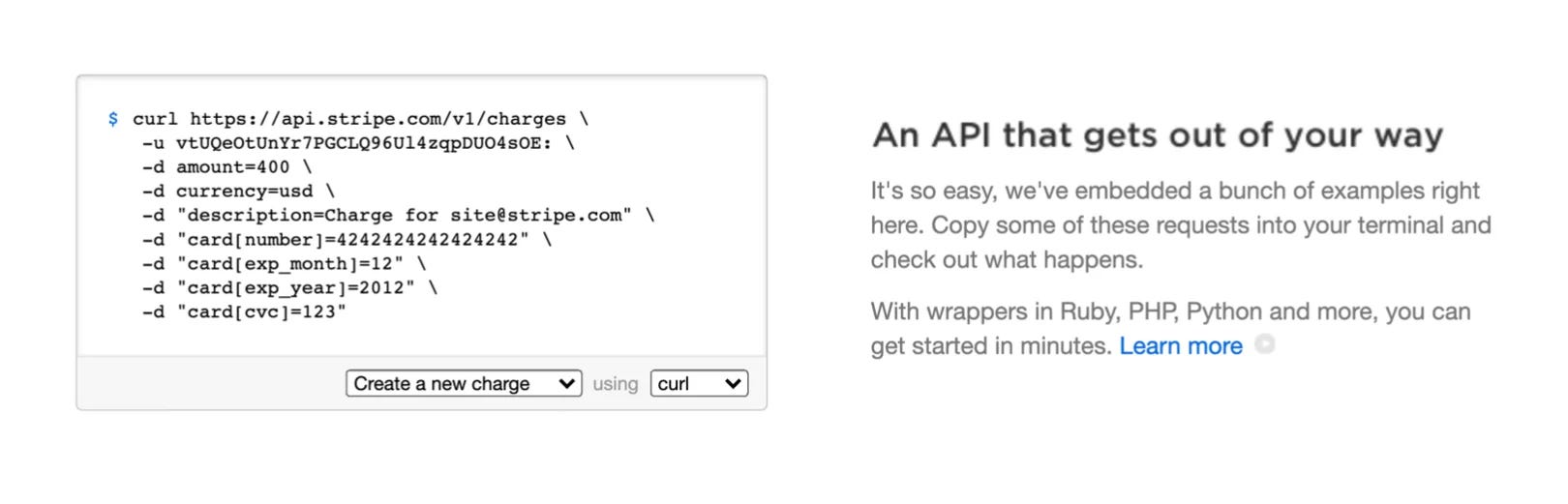

Stripe offers a perfect example. Today, they process payments for businesses of every size and type, from startups to Fortune 500 companies, online and increasingly offline. They're one of the most valuable private companies in the world.

But they didn't start there. Stripe's initial wedge was elegantly narrow: developers who wanted to accept payments with minimal friction. The famous "accept payments in seven lines of code" positioning was a laser focus on solving a specific problem for a specific audience. Their early users were predominantly Y Combinator companies and similar startups where technical founders made purchasing decisions.

This narrow focus had several advantages. The product could be optimized for developer experience rather than enterprise procurement processes. Distribution happened through word-of-mouth in tight-knit developer communities. Integration was so simple that switching costs for experimentation were minimal, allowing rapid adoption.

From that foundation, Stripe could systematically expand. First to larger startups, then to established tech companies, then to traditional enterprises, and eventually to physical retail and end-to-end financial services. Each expansion built on the previous one, with the core product evolving to serve new use cases while maintaining the developer-friendly DNA that made them successful initially.

The pattern isn't limited to software. Consider Vineyard Vines, which started by selling ties—just ties. Not clothing, not a lifestyle brand, not a full wardrobe solution. Ties with distinctive patterns that were more affordable than Ferragamo but appealing to a specific demographic.

That narrow wedge allowed them to establish brand identity, build distribution relationships, and create customer loyalty. Once they owned that category for their target audience, expanding into shirts, pants, and eventually a full clothing line was a natural evolution. The same customers who trusted them for ties became buyers of their broader product range.

Under Armour followed a similar path. They started with performance undershirts designed for athletes in specific weather conditions. They focused on one category where they could be demonstrably better than alternatives. That narrow focus on performance and a specific use case gave them credibility that enabled expansion into a full-body athletic brand.

Yeti built their brand on premium coolers, a product category that barely seemed worthy of innovation. But by being the absolute best at that one thing—coolers that could keep ice frozen for days in extreme conditions—they created a loyal customer base that would follow them into drinkware, bags, and outdoor accessories. The narrow wedge established the brand's premium positioning and performance credentials.

Perhaps the most striking example is NVIDIA. Fifteen years ago, they were primarily a gaming GPU company. High-performance graphics chips for gaming PCs and devices. It was a narrow, specialized market with demanding customers and clear performance metrics.

That specialization created an edge in GPU architecture and manufacturing that proved transferable to other compute-intensive applications. This success stemmed from strategic foresight rather than fortunate timing. Jensen Huang and the NVIDIA team recognized early that the future of computing would shift toward accelerated compute workloads. Their lengthy head start in GPU development and the scalable platform architecture they built gave them an insurmountable advantage when the market began its migration.

When the AI revolution emerged and the industry recognized that GPUs were ideal for machine learning workloads, NVIDIA was already years ahead. Rather than pivoting to AI, they were applying existing capabilities to an adjacent market where their core strengths were suddenly invaluable. The narrow wedge of gaming GPUs had given them both the technical foundation and the manufacturing scale to dominate an entirely new category.

Today, depending on the day, NVIDIA is the most valuable company in the world, powering everything from data centers to autonomous vehicles. That dominant position was built on years of focused execution in a narrower market that seemed much less consequential at the time, combined with visionary leadership that anticipated where computing was headed.

This pattern has important implications for how startups should think about market opportunity and product strategy. The temptation to target large markets immediately is understandable, especially in fundraising contexts where TAM matters. But execution reality favors a different approach.

When you position your product as universally applicable, you create unexpected friction. Buyers don't know what to do with a solution that claims to solve every problem. Even ChatGPT faced this issue to an extent. Where their growth went truly vertical was when their image generation model went viral and mainstream, non-AI-inclined users now saw a personal use case for this generalized intelligence - to make their friends look like cartoons. It’s an example where the generalist approach paradoxically makes selling harder, not easier.

Founders often feel a sense of relief when they decide to be ruthlessly specific about who they serve and what problem they solve. "We are a company that does X and solves Y problem for companies like this." That clarity makes everything easier: customer acquisition, product development, messaging, partnerships. Customer qualification is simplified, with less cycles spent pitching the wrong buyers. And buyers can quickly assess fit, and early customers become reference accounts for similar prospects.

This doesn't mean building a narrow product with limited capabilities and upside. The examples above show you can architect for broader applicability while going to market with vertical or functional focus. The back-end might be a flexible platform guided by your intuition around how markets evolve over time. But your initial positioning and GTM motion should be sharp and targeted.

The narrow wedge creates optionality. Once you own your initial segment, you can choose between two valuable paths.

The first is systematic expansion. Use your foothold to attack adjacent markets, either by extending your product or by leveraging brand and distribution to serve related needs. This is the path Stripe took: start with developers, expand to enterprises. It requires capital and operational capability to execute multiple go-to-market motions, but it can build enormous businesses.

The second is vertical dominance. Decide that the narrow market you're serving is actually quite attractive, and focus on being the absolute best solution for that segment. Build deep features and workflows specific to that industry. Become so embedded in customer operations that switching is unthinkable. This can create highly profitable, defensible businesses even in markets that seem small initially.

Both outcomes can be excellent. The key is being honest about the capital intensity, funding partners, competitive dynamics, and operational complexity of each path. But you need to win the narrow wedge first before either option is available. And I think that early stage capital markets are going to need to evolve to better support option two over the next several years, as AI is increasingly creating a set of capital efficient, vertical champions.

The fundamental insight is that market expansion is something you earn, not something you claim. Customers don't care about your vision of being a platform that serves everyone. They care about whether you can solve their specific problem better than alternatives.

By starting narrow, you prove you can deliver value. You build product velocity, customer relationships, and market credibility. You develop the operational capabilities and financial resources needed to expand. And you create the customer base that can pull you into adjacent markets based on their needs rather than your assumptions.

The companies that become broad platforms almost never start that way. They start by being exceptional at one thing for one audience. Then they systematically earn the right to do more.

For founders evaluating their strategy, the question isn't whether your eventual market is large enough. It's whether you can identify a narrow wedge where you can become the clear leader, and whether that wedge provides the foundation for the business you want to build. Start small, win decisively, then expand from strength. It's a less exciting pitch than targeting everyone immediately, but it's how many enduring companies are actually built.